雅思閱讀機(jī)經(jīng)還原:Tasmanian tiger Extinction Is Forever?

2017/5/23 17:20:31來源:新航道作者:新航道

摘要:雅思閱讀機(jī)經(jīng)還原:Tasmanian tiger Extinction Is Forever?

Tasmanian tiger Extinction Is Forever?

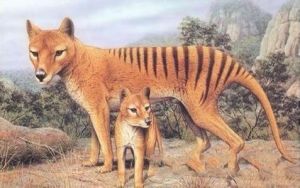

“Danger, “ says the sign on the door of a laboratory at the Australian Museum in Sydney: “Tasmanian Tiger, Trespassers will be eaten!” The joke is that the Tasmanian tiger—a beloved symbol of the island state that appears on its license plate—has been extinct for nearly seven decades. But researchers behind that door are working to bring the animal back to life by cloning it, using DNA extracted from specimens preserved decades ago. Among other things, the work raises questions about the nature of extinction itself. A The Tasmanian tiger’s Latin designation, Thylacinus cynocephalus, or “dogheaded pouched-dog,” makes it redundantly clear that the marsupial’s feline nickname is a misnomer. Yet its striped coat was cat-like, which runs nearly shoulder to tail. The animal had large, powerful jaws, which secured the predator a place atop the local food chain. Females carried their young in backward-facing pouches. Thylacines, once spread throughout mainland Australia and as far north as New Guinea, were probably outcompeted for food by the dingoes ( 獵狗) that humans introduced to the area some 4,000 years ago, says Australian Museum director Mike Archer, founder of the cloning project. Eventually, thylacines remained only on the dingo-free island of Tasmania, south of the mainland. But with the arrival of European settlers in the 1800s, the marsupial’s days were numbered. Blamed (often wrongly) for killing livestock, the animals were hunted indiscriminately. The government made thylacines a protected species in 1936, but it was too late; It was a frigid winter night in 1936. A lone Tasmanian tiger huddled in his— or her— open enclosure at Hobart Zoo. With nowhere to shelter from the cold and no keepers to care, the delicately striped animal died. When this solitary animal—whose sex was not even recorded because of lack of interest—died, so did an entire species, the last specimen reportedly died in captivity the same year. What’s more, with the passing into extinction of the Tasmanian tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus, it was the end of the line for an entire family of marsupials that had lived in Australia for millions of years.

The Australian researchers set out to bring the animal back partly to atone for humanity’s role in its extinction, Archer says. The idea took root 15 years ago when he saw a pickled thylacine pup in the museum’s collection. “It jarred me and started me thinking,” recalls the 58-year-old paleontologist and zoologist, who received his undergraduate degree from Princeton University and his doctorate from the University of Western Australia. “DNA is the recipe for making a creature. So if there is DNA preserved in the specimen, why shouldn’t we begin to use technology to read that information, and then in some way use that information to reconstruct the animal? I raised the issue with a geneticist. The response was derisive laughter.”

Then, in 1996, Dolly the sheep burst onto the scene and, suddenly, Archer says, “cloning wasn’t just a madman’s dream.” Dolly proved that DNA from an ordinary animal cell— in her case, a ewe’s udder— could generate a virtually identical copy, or clone, of the animal after the DNA was inserted into a treated egg, which was implanted in a womb and carried to term. Archer’s goal is even more ambitious: cloning an animal with DNA from long-dead cells, reminiscent of the sci-fi novel and movie Jurassic Park. The challenge? The DNA that makes up the chromosomes in which genes are bundled falls apart after a cell dies.

Researchers working with Don Colgan, head of the museum’s evolutionary biology department, extracted DNA from a thylacine pup preserved in alcohol in 1866, and biologist Karen Firestone obtained additional thylacine DNA from a tooth and a bone. Then, using a technique called polymerase chain reaction, the researchers found that the thylacine DNA fragments could be copied. The scientists next have to collect millions of DNA bits and pieces and create a “l(fā)ibrary” of the possibly tens of thousands of thylacine genes— a gargantuan task, they concede. Still, an even greater obstacle looms, that of stitching all those DNA fragments together properly into functioning chromosomes; the scientists don’t know how many chromosomes a thylacine had, but suspect that, like related marsupials, it had 14. But no scientist has ever synthesized a mammalian chromosome from scratch. If the Aussie scientists accomplish those feats, they may try to generate a thylacine by placing the synthetic chromosomes into a treated egg cell of a related species— say, a Tasmanian devil, another carnivorous marsupial—and implant the egg in a surrogate mother.

Such cross-species cloning, as the procedure is called, is no longer fantasy. In 2001, Advanced Cell Technology (ACT) of Worcester, Massachusetts, succeeded in cloning, for the first time, an endangered animal, a rare wild ox called a gaur. This past April, scientists from ACT, Trans Ova Genetics of Sioux Center, Iowa, and the Zoological Society of San Diego announced they had cloned a banteng, an endangered wild bovine species native to Southeast Asia, using a domesticated cow as a surrogate mother. Meanwhile, researchers in Spain are trying to clone an extinct mountain goat, called a bucardo, using cells collected and frozen before the species’ last member died in 2000. Other scientists hope to clone a woolly mammoth from 20,000-year-old specimens found in Siberian permafrost.

Many scientists are skeptical of the thylacine project. Ian Lewis, technology development manager at Genetics Australia Cooperative Ltd., in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, Australia, says the chances of cloning an animal from “snippets” of DNA are “fanciful.” Robert Lanza, ACTs medical director and vice president, says cloning a thylacine is beyond existing science. But it may be within reach in several years, he adds: “This area of genetics is moving forward at an exponential rate.”

In Australia, critics say the millions of dollars that the thylacine project will cost would be better spent trying to save endangered species and disappearing habitats. One opponent, Tasmanian senator and former Australia Wilderness Society Director Bob Brown, says people might become blase about conservation if they’re lulled into thinking a lost species can always be resurrected. The research “feeds the mind-set that science will fix everything,” he says. Another concern touches on the great nature-nurture quandary: Would a cloned thylacine truly represent the species, given that it would not have had the chance to learn key behaviors from other thylacines? For some carnivores, says University of Louisville behavioral ecologist Lee Dugatkin, “it’s clear that young individuals learn various hunting strategies from parents.” And a foster parent might not fill the gap. Dugatkin asks whether a cloned Tasmanian tiger raised by a surrogate Tasmanian devil would just be a devil in tiger’s clothing.

But Archer says, in effect, a thylacine is a thylacine, however its DNA blueprint is obtained, because much animal behavior, including that of marsupials, is genetically hardwired or instinctual. We take kittens and raise them with humans, but they still behave like cats,” he points out. And Archer, who envisions nature preserves populated by cloned thylacines and their offspring, says the project is actually a boon to conservation: it shows what it takes just to contemplate resurrecting a vanished species. For now, Archer and coworkers are trying to piece together the thylacine’s exact genetic makeup.

雅思閱讀機(jī)經(jīng)還原:

維京古沉船的研究 Viking Voyage

免費(fèi)獲取資料

熱門搜索: 上海雅思培訓(xùn)哪家好| 上海雅思封閉班| 上海雅思一對一培訓(xùn)| 雅思全日制培訓(xùn)| 上海新航道| 2022年雅思寫作話題題庫+范文|

熱報課程

- 雅思課程

| 班級名稱 | 班號 | 開課時間 | 人數(shù) | 學(xué)費(fèi) | 報名 |

|---|

免責(zé)聲明

1、如轉(zhuǎn)載本網(wǎng)原創(chuàng)文章,情表明出處

2、本網(wǎng)轉(zhuǎn)載媒體稿件旨在傳播更多有益信息,并不代表同意該觀點(diǎn),本網(wǎng)不承擔(dān)稿件侵權(quán)行為的連帶責(zé)任;

3、如本網(wǎng)轉(zhuǎn)載稿、資料分享涉及版權(quán)等問題,請作者見稿后速與新航道聯(lián)系(電話:021-64380066),我們會第一時間刪除。

全真模擬測試

雅思動態(tài)

DeepSeekx雅思官方:中國考生...

制作:每每